Russia Chemical Overview

About the image

Background

This page is part of the Russia Country Profile.

- Click for Recent Developments and Current Status

From the early 1920s through the early 1990s, the Soviet Union developed, produced, stockpiled and deployed chemical weapons (CW).

The USSR’s CW program produced most types of known chemical warfare agents in immense quantities, and developed the world’s largest chemical warfare infrastructure. At its height, the Soviet chemical warfare infrastructure involved 4 research facilities, 2 test facilities, and 8 storage facilities. Following the fall of the Soviet Union, Russia became involved with U.S. Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) programs aimed at destroying chemical warfare agents and converting chemical warfare infrastructure and personnel into civilian roles; the CTR agreement expired in 2013 and Russia signed a new bilateral Protocol with the United States. 1 Despite decades of efforts by Russia, the CTR program, and the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), challenges persist in eliminating what was at one time a vast stockpile. 2

Capabilities

The Soviet Union’s CW program involved the army, industry, and the health system, thus encompassing an extensive secret military-chemical complex of 35-40 facilities. The Administration of the Chief of Chemical Forces (UNKhV), which was housed within the Ministry of Defense (MOD), was responsible for CW affairs and had its own research and testing facilities. 3 The leading research facilities were the Military Academy of Chemical Protection (VAKhZ) of the Red Army in Moscow, the Central Scientific Research Military Technology Institute, and the Central Military-Chemical Proving Grounds at Shikhany, on the banks of the Volga River. 4 The Red Army also tested experimental chemical weapons near the Caspian Sea, Lake Baikal, Florishchi (near Nizhniy Novgord), Gelendizhik, and Luga (Leningrad oblast).

As to industry, the Soyuzorgsintez All-Union Association included chemical weapons plants and research facilities; it also directed production of chemical weapons through the late 1980s and weapons development until 1 January 1993. The key institute of the chemical industry in developing chemical weapons was the State Union Scientific Research Institute of Organic Chemistry and Technology (GSNIIOKhT). 5

The Ministry of Health (MOH) provided sanitation and health support to the CW program through the Institutes of Labor Hygiene and Occupational Illnesses in Moscow and Nizhniy Novgorod. The MOH was also involved in the development of new generations of chemical weapons at the Institutes of Labor Hygiene and Occupational Pathology in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) and Volgograd.

The Ministry of Agriculture chiefly supported the development of herbicides for weapons use. The Moscow All-Union Scientific Research Institute of Chemical Means of Plant Protection (VNIIKhSZR), Herbicidal Institute in Ufa, and Experimental Plant in Shchelkovo developed formulas for killing crops possessed by a “likely enemy.”

Chemical weapons were produced on the shores of deep rivers, using the waters of the Volga, Oka and Kama rivers for production needs, as well as for the disposal of waste. The production plants were located in Moscow, Volsk (Saratov oblast), Chapayevsk (Samara oblast), Berezniki (Perm oblast), Novomoskovsk (Tula oblast), Volgograd, Dzerzhinsk (Nizhniy Novgorod oblast), Zavolzhsk (Ivanovo oblast), and Novocheboksarsk (Chuvash Republic). 6

History

1914 to 1941: Lessons from the Eastern Front of World War I

Russia was unprepared for Germany’s introduction of chemical weapons in World War I. The Germans first attempted to use chemical weapons on a large scale at the Battle of Bolimov, Russia on February 1915. Fortunately for the Russian Imperial Army, the frigid temperatures caused the German-launched poisonous gas to freeze and drop to the ground, rendering it ineffective against Russian troops. 7 Germany’s first successful use of lethal chemical weapons at the Second Battle of Ypres later that year forced Russia to develop chemical warfare countermeasures, indigenous offensive capabilities, tactics, and doctrines. 8

Russian chemical weapons defense primarily focused on utilizing gas masks. Design flaws in indigenously-produced gas masks, and a shortage of more effective British-made masks resulted in insufficient supplies for Russian troops. 9 Consequently, the Russian army suffered more than twice the casualties from chemical weapons than any other army. 10 In addition to creating chemical weapons defense measures, Russia attempted to increase its own offensive chemical weapons capacity. However, efforts to produce chemical weapons agents and delivery mechanisms lagged behind German efforts. Russian chemical weapons agent production capabilities equated to only 2.4% (3,650 of 150,000 tons) of the aggregate amount produced by all combatants, and 4.2% of the total amount of chemical weapons used in the war. 11 Russia’s chemical weapons agent production consisted of chlorine, phosgene, chloropicrin, and some tear and blood agents. However, the country never developed or produced mustard or ethyldichloroarsine gas due to insufficient technological advancement. 12 Russia’s inability to produce enough chemical agents to mount an effective chemical weapons counterattack eventually necessitated ordering additional chemicals from the British. 13

Russia withdrew from the First World War following the October Revolution, when the Bolshevik party seized control of the national government, and later defeated the loyalist opposition in the Russian Civil War. In 1917, the Soviet military concluded that chemical weapons were “an extremely powerful and beastly weapon,” and that “their own technical inferiority had placed them at a terrible disadvantage.” 14 In 1928, Joseph Stalin, General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the leader of the Soviet Union, took two major steps that revitalized the Soviet Union’s chemical weapons program: he created the Military Chemical Administration to oversee the chemical weapons program, and implemented the First 5 Year Plan (1928-1932) to rebuild Russia’s industrial capabilities. 15 Heavy investment in the Soviet chemical industry caused the Soviet Union’s chemical production to increase rapidly, from 5% of global production in 1929 to 18.5% in 1936. 16

In addition, the Soviet Union took advantage of German expertise to enhance its chemical weapons capabilities. The Treaty of Versailles’ terms forbade Germany from importing or producing chemical weapons. 17 The Soviet Union fed off of Germany’s concerns that its chemical weapons expertise would become antiquated to secure Germany’s participation in the Tomsk Project, in which and the USSR allowed the Germans to produce some chemical weapons in exchange for assistance building the facilities. 18 German chemical weapons scientists introduced Soviet scientists to better technology and production processes at the joint-venture facility in Shikhany.

By the 1930s, the Soviet chemical weapons program no longer lagged behind those of other industrial powers. The Soviet Union produced chemical weapons agents such as yperite (sulfuric mustard gas), nitric, lewisite, prussic acid, phosgene, diphosgene, adamsite, diphenyldichloroarsine, diphenylcyanoarsine, chloroacetophenone, CS gas, and chloropicrin. 19 Additionally, the Soviet Union had a “cheap and useful means for engaging large area targets and obtaining high casualty rates, and for contaminating the ground.” 20 The Red Army at this time was “organizationally and doctrinally prepared to employ chemical weapons.” 21

1941 to 1953: The Great Patriotic War and Late-Stalinist Military Doctrine

Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 took the country by surprise. Although the Soviets had accumulated a vast chemical weapons stockpile during the interwar years, they did not employ chemical weapons to halt the German invasion. The Germans estimated that the Soviets had produced 8,000 tons of chemical weapons agents per month before the invasion, meaning the Red Army had the capability to use chemical weapons to stop or stall German advancement. 22

However, the Red Army was caught off guard, and an organized retreat with chemical weapons was impossible. The deteriorated state of the Red Army’s chemical discipline hampered its ability to organize and transport toxic substances. As a result, the advancing German forces were able to seize the advanced stores of the Military Chemical Administration. If the Soviet Union had used chemical weapons first without access to its vast stockpiles, production capabilities, and the discipline to restart production in a timely manner, German retaliation with chemical weapons would have harmed the Soviet Union more than forgoing the chemical option. 23 Moreover, Stalin wanted U.S. President Roosevelt to start military operations in Western Europe to help alleviate fighting on the Eastern Front, but Stalin worried that U.S.-Soviet relations would suffer if the Red Army struck first with chemical weapons because Roosevelt disliked chemical weapons. 24

While advancing towards Germany in the final stages of the war, the Red Army captured the nerve agent factory at Dyhrenfurth, Poland, complete with manufacturing lines, filling lines, stores of raw materials, and several gallons of tabun. 25 This acquisition was significant to the Soviet program because it fueled more experimentation and testing of new agents. 26 The Dyhrenfurth factory was packed and shipped to Stalingrad, where Soviet scientists learned that tabun production was simpler than sarin production. 27 The Soviet Union started tabun production in 1946, and by 1948 it was listed in its inventory of chemical weapons agents. 28 The Soviets also copied the Dyhrenfurth factory’s design when they built Chemical Works Number 91, which could produce 2,000 tons of chemicals per month. The Soviet Union disguised the factory as a commercial facility by splitting chemical production between chemical weapons agents (35%) and commercial items (65%). 29

1953 to 1964: Post-Stalin Doctrinal Debate

Starting in the mid-1950s, the Red Army’s observation of NATO forces, which appeared to be focused primarily on nuclear warfare, prompted them to pursue a mobile and flexible army that could adapt to multiple scenarios. 30 Soviet Marshall Georgi Zhukov said in a speech to the 20th Party Congress, “[A]ny new war will be characterized by mass use of air power, various types of rocket, atomic, thermo-nuclear, chemical and biological weapons,” in an effort to promote military doctrinal change. 31

U.S. Army Major General Marshall Stubbs estimated that in 1959 the Soviet Union possessed modern and efficient chemical weapons, sufficient protective chemical equipment for large-scale warfare, and plentiful decontamination equipment. 32 Soviet Marshall Vasily Sokolovsky’s 1962 Military Strategy guide, in which he “recommended [chemical weapons integration] frequently within the framework of various tactical operations,” reflected Stubbs’ assessment. 33 Sokolovsky believed chemical weapons could inflict significant casualties, hamper troop movements, and impede enemy activities if employed in a large surprise attack. Such a scenario became more conceivable in 1959, when the Soviet Union began production of sarin on an industrial scale. 34

1965 to 1985: The Re-Emergence of Non-Nuclear Warfare

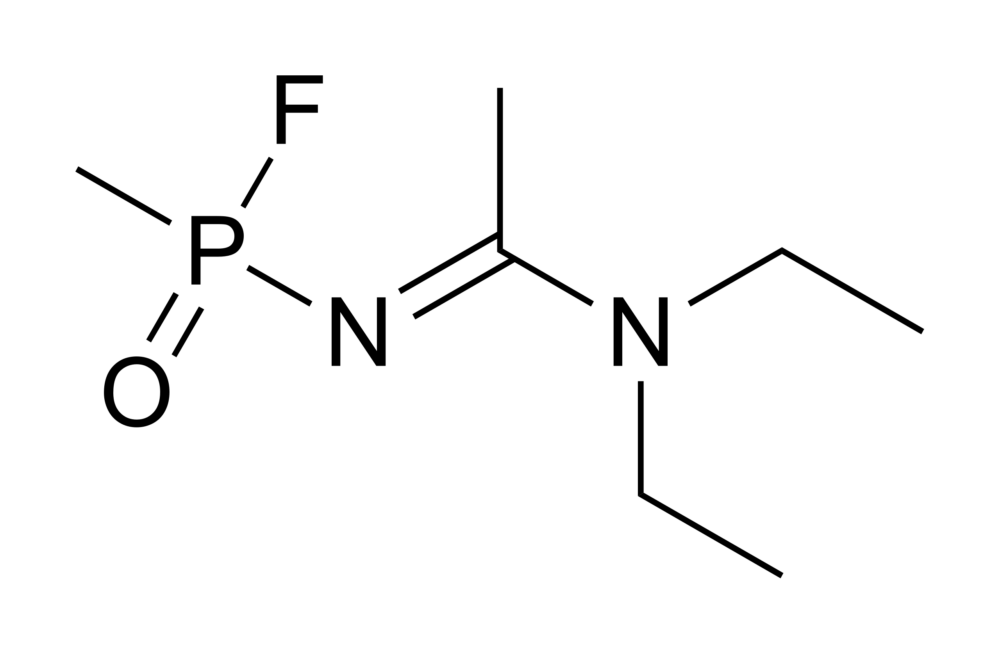

Soviet doctrine and strategy anticipated that in a conflict between NATO and the Warsaw Pact, chemical weapons would be the first WMD used in the European operational theater. This view led to major chemical weapons research, development, and production from the 1960s to the 1980s. 35 Major developments included the production of soman in 1967, V-agents in 1972, and the creation of additional production and storage facilities in Volgograd, Novocheboksarsk, Zaporozhye, Pavlodar, and Volsk in the early 1980s under the guise of Khimprom industrial chemical factories. 36 During the 1970s, the Soviets experimented with binary agents but failed to create a successful binary agent design. 37 However, in the 1980s Soviet scientists tried again using ordinary chemicals that might be used in fertilizers or pesticides, resulting in the Foliant project that led to the novichok (“newcomer”) series of nerve agents. The novichok agents’ structure was slightly different than VX, but was 5 to 10 times more toxic. 38 For a listing of Russia’s alleged undeclared “Novichok” capabilities, see Table 3.

Soviet chemical weapons doctrine changed to accommodate an increase of supply and new weapons. According to a U.S. Army assessment, it appeared that the Soviet Union would use chemical weapons “early in an operation or from its onset. 39 During an advance of Warsaw Pact forces, non-persistent agents would be used against enemy troop positions, areas of occupation, and installations that Soviet forces wanted to occupy. 40 The Eastern bloc forces would use chemical weapons in conjunction with conventional strikes to neutralize NATO’s nuclear capability, command and control, and aviation. 41 The combined use of chemical weapons and conventional armaments was intended to inflict large casualties and to force enemy combatants to conduct operations in “hot and cumbersome protective clothing,” which would hurt morale and efficiency. 42 Additionally, if the Soviet Union had to use nuclear weapons to expedite operations, chemical weapons would be used in places that were not attacked with nuclear weapons. 43 While Warsaw Pact forces advanced, persistent agents would be used to protect their flanks. 44 This chemical weapons doctrine aimed to rapidly overpower enemy forces, through non-nuclear means, and to neutralize enemy tactical nuclear capabilities.

In 1982, the United States accused the Soviet Union of utilizing chemical in Afghanistan, Laos, and Cambodia. 45 However, the U.S. failed to galvanize world opinion, and had insufficient evidence to prove the Soviet Union had actually used chemical weapons in these regions. As a result, the Soviet Union’s alleged use of chemical weapons became a point of dispute between the Reagan Administration and the USSR. 46 However, this confirmed the U.S. Army’s assessment that the Soviet Union had no reservations regarding the use of chemical weapons. 47

The Soviet Union supplied a number of states with chemical weapons expertise, knowledge, agents, and technology from the 1960s to the 1980s. In the 1960s, Egypt was the first country to receive Soviet assistance; high-ranking Egyptian officers trained at the Soviet Red Banner Academy of Chemical Defense, and Egypt received chemical weapons “materials.” In the mid-1960s Iraq received limited chemical weapons training. The Soviet Union provided Syria with the chemical agents, delivery systems, and training necessary to create domestic chemical weapons capabilities. Libya was the largest buyer of Soviet military assistance, and may have received chemical weapons indoctrination, training, and small amounts of chemical weapons agents from the then-Soviet satellite state of Poland in 1980. 48

1985 to 1996: Glasnost, Perestroika, and the Wyoming Memorandum of Understanding

Mikhail Gorbachev’s rise to power and policies of glasnost and perestroika initiated internal reforms in the Soviet Union and a thawing of relations with the West. On 13 April 1987, Gorbachev announced in Prague that the Soviet Union would stop manufacturing chemical weapons. From 3-4 October 1987, 110 experts from 45 countries and 55 journalists visited Shikhany to see chemical munitions such as grenades, rockets, artillery rounds, and a Scud missile warhead. Minister of Foreign Affairs Eduard Shevardnadze and the Soviet arms control representative Yuri Nazarkin sought to build an atmosphere of trust, and to demonstrate that the Soviet Union had “nothing to hide.” Despite the officially stated intention to open up the Soviet chemical weapons program, experts and journalists were not shown the novichok agents. 49

In 1989, the Soviet Union and the United States signed the Wyoming Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), which called for information sharing and verification inspections for chemical weapons. 50 Phase I of the MOU involved mutual data exchanges regarding chemical weapons production facilities, destruction facilities, storage areas, capabilities, types of agents, and the aggregate quantity of agents. The Soviet Union declared large chemical production complexes at Chapayevsk, Dzerzinsk, Volgograd, and Novocheboksarsk. 51] From June to August 1990, each side visited the declared chemical weapons facilities. At the beginning of the inspections, U.S. President George H.W. Bush and Gorbachev signed the Bilateral Destruction Agreement (BDA) on 1 June 1990, which called on each state to begin destroying its chemical weapons stockpiles. 52 Phase II of the MOU began in 1994, with the countries exchanging data in April and May, and inspections occurring between August and December. This phase involved further information sharing on chemical weapons stockpiles, as well as development, production, and storage facilities, and was intended to be an indicator of U.S. and Russian approaches to data declarations under the BDA and CWC. 53

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the newly formed Russian Federation inherited the Soviet Union’s military programs, including the chemical warfare sector. The State Institute of Organic Chemical Technology (GosNIIOKhT) was the primary organization that researched, developed, and tested chemical agents and munitions. GosNIIOKhT employed approximately 6,000 people, who worked in Novocheboksarsk (nerve agent production), Volgograd (nerve agent production), Dzerzinsk (blister agent production), Shikhany (testing), and Nukus (testing, located in the newly independent state of Uzbekistan). 54 The Russian government alarmed the international community by stating that it could not afford to keep the facilities open or personnel employed. 55

The U.S. Congress resolved to assist Russia and other former republics of the Soviet Union in their efforts to dismantle their chemical weapons stockpiles and prevent the proliferation of chemical weapons agents, technology, and expertise through the CTR program, established in 1991. 56 CTR’s chemical weapons nonproliferation mandate was to neutralize the weapons, destroy or convert production facilities, establish safeguards at research facilities, and provide employment to former chemical weapons scientists. 57 However, by 1995 some U.S. members of Congress began to question the national security benefits of CTR, citing a perceived lack of tangible results regarding chemical weapons elimination and general mistrust of Russia’s motives. 58

CTR also established the Science Centers Program. 59 This Program provided resources to launch and continuously fund two international science and technology centers: the International Science and Technology Center in Moscow (ISTC), and the Science and Technology Center in Ukraine (STCU). The ISTC is an intergovernmental organization, which connects former WMD scientists from Russia and the FSU with their Western colleagues, enabling international scientific projects by promoting cooperation in the area of R&D with the goal of redirecting FSU scientists’ research and talents towards peaceful yet commercially viable projects. 60

American suspicion of Russia’s intentions was fueled by a series of events, starting on 10 October 1991, when Dr. Vil Mirzayanov wrote an article titled Inversion, which disclosed the existence of the novichok agent program and the continued progress of the Russian chemical weapons program. 61 On 16 September 1992, Mirzayanov co-authored an additional article with a colleague, Lev Fyodorov, which described the continuation of testing in Uzbekistan and production of Novichok agents in Volgograd. 62 Mirzayanov and Fyodorov’s accounts of continued chemical weapons activity corresponded with a U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) assessment, which asserted the following: the Russians declared a CW stockpile of 39,927 metric tons (MT), despite estimates by Soviet chemical weapons scientists and the intelligence community of 50,000 to 70,000 tons; the Russians did not declare all chemical weapon munitions, agents, development, production, and storage facilities; information from declared facilities was incomplete; inspectors were denied access to facilities; and facilities declared in Phase I were not disclosed in Phase II despite retaining operational capacity. 63 These problems developed in complexity as disagreements within the Russian government became apparent. On 7 April 1994, Russian President Boris Yeltsin fired the chairman of the Committee on Problems of Chemical and Biological Disarmament, and forced army general Anatoly Kuntsevich into retirement. 64 The firing of Kuntsevich fed into concerns of Russian mismanagement and insincerity regarding chemical weapons disarmament.

1997 to the Present: Chemical Weapons Convention Ratification and Chemical Weapons Destruction

In 1997, the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) entered into force and further solidified Russian commitments to chemical weapons disarmament and nonproliferation. 65 However, a number of problems hampering disarmament and nonproliferation efforts persisted. By the mid to late 1990s, 3,500 chemical weapons scientists and 10 chemical weapons facilities remained “high-risk proliferation concerns” because either the Russian government delayed grant approval for transitioning chemical weapons scientists and facilities into peaceful avenues, or the approved funds became unaccountable. 66 Physical security of facilities containing chemical weapons munitions or agents also became a concern. In 1997, the U.S. Congress passed the Defense Authorization Act of 1997 (DAA), which provided funding for “safeguards over materials and technology associated with weapons of mass destruction,” such as access control measures (e.g., locks and perimeter fencing), because Russian security at those facilities had deteriorated significantly. 67 At the same time, the Russian economy was in crisis, so the DAA allocated funds to help Russia build chemical destruction plants and facilitate chemical agent elimination. 68

Russia’s chemical weapons destruction and peaceful conversion efforts started to have tangible effects by the 2000s. Additional funding from the United States, the G-8’s Global Partnership Against the Spread of Weapons and Materials of Mass Destruction, and the member states of the CWC allowed Russia to begin chemical weapons elimination, to finance peaceful research by former weapons scientists, and to plan the construction of new chemical weapons destruction facilities. 69 From 1999 to 2002, the OPCW approved 16 requests by Russia to use former chemical weapons facilities at Novocheboksarsk, Volgograd, Dzerzhinsk, Chapoevsk, and Bereziki for peaceful purposes. 70 By 2009, three chemical weapons destruction facilities were in operation using neutralization and incineration techniques: Gorny in 2002, Maradykovsky in 2006, and Shchuchye in 2009. 71 The OPCW reported that Russia had eliminated 12,169 metric tons (30.25%) of declared Category 1 chemical weapons by April 2009. 72

Recent Developments and Current Status

On 10 October 2012, the Russian government announced its intention not to renew CTR programs in Russia. A statement on the Russian Foreign Ministry website claimed that “American partners know that their proposal is not consistent with our ideas about what forms and on what basis further cooperation should be built.” 73 Additionally, it noted that Russia is now financially able to support domestic nonproliferation efforts. Senator Lugar’s visit to Russia in August 2012 failed to convince his Russian counterparts to renew the agreement. 74

Following Russia’s aforementioned decision to permit the CTR’s expiration in 2012, the U.S. and Russia were able to sign a bilateral Protocol on 14 June 2013, three days before the expiration of the Nunn-Lugar CTR Umbrella Agreement. 75 The bilateral Protocol restored the 2003 Multilateral Nuclear Environmental Program in the Russian Federation (MNEPR). Although the MNEPR and the associated Protocol prolong Russo-American mutual assistance for nuclear security, it does not encompass the previously covered dismantling of ballistic missiles and chemical weapons. 76 Under the MNEPR and the June 2013 Protocol, Russia will assume the financial burden and total responsibility for upholding its duties to the OPCW, by continuing to eliminate its chemical weapon arsenal. 77

Russia planned to facilitate further destruction of Category 1 chemical weapons by gradually opening new destruction facilities on an “as needed basis” to ensure that each facility is suitable for handling particular chemical weapons agents. A new chemical weapons destruction facility opened at Kizner in December 2013, operating in conjunction with the facilities in Leonidovka, Maradykovsky, Pochep, and Shchuchye. 78 As of March 2015, Russia had destroyed 86% of its declared chemical weapons. 79 The destruction at the Leonidovka, Maradykovsky, Pochep, and Shchuchye facilities is scheduled to be completed by the end of 2015; only the Kizner facility will continue the destruction work. 80 Because Russia needed additional time to destroy its remaining stockpile of chemical weapons, its deadline to complete destruction efforts was extended to December 2020. 81

Stay Informed

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest on nuclear and biological threats.

Glossary

- Deployment

- The positioning of military forces – conventional and/or nuclear – in conjunction with military planning.

- Chemical Weapon (CW)

- The CW: The Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons defines a chemical weapon as any of the following: 1) a toxic chemical or its precursors; 2) a munition specifically designed to deliver a toxic chemical; or 3) any equipment specifically designed for use with toxic chemicals or munitions. Toxic chemical agents are gaseous, liquid, or solid chemical substances that use their toxic properties to cause death or severe harm to humans, animals, and/or plants. Chemical weapons include blister, nerve, choking, and blood agents, as well as non-lethal incapacitating agents and riot-control agents. Historically, chemical weapons have been the most widely used and widely proliferated weapon of mass destruction.

- Cooperative Threat Reduction (Nunn-Lugar) Program

- A U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) program established in 1992 by the U.S. Congress, through legislation sponsored primarily by Senators Sam Nunn and Richard Lugar. It is the largest and most diverse U.S. program addressing former Soviet Union weapons of mass destruction threats. The program has focused primarily on: (1) destroying vehicles for delivering nuclear weapons (e.g., missiles and aircraft), their launchers (such as silos and submarines), and their related facilities; (2) securing former Soviet nuclear weapons and their components; and (3) destroying Russian chemical weapons. The term is often used generically to refer to all U.S. nonproliferation programs in the former Soviet Union—and sometimes beyond— including those implemented by the U.S. Departments of Energy, Commerce, and State. The program’s scope has expanded to include threat reduction efforts in geographical areas outside the Former Soviet Union.

- Bilateral

- Bilateral: Negotiations, arrangements, agreements, or treaties that affect or are between two parties—and generally two countries.

- Phosgene (CG)

- Phosgene (CG): A choking agent, phosgene gas causes damage to the respiratory system leading to fluid build-up in the lungs. Phosgene also causes coughing, throat and eye irritation, tearing, and blurred vision. A gas at room temperature, phosgene can be delivered as a pressurized liquid that quickly converts to gas. Germany and France used phosgene during World War I; the United Kingdom, the United States, and Russia also produced military phosgene. Phosgene caused over 80% of the deaths from chemical gas during World War I.

- Blood agent

- Blood agents are chemical agents that enter the victim’s blood and disrupt the body’s use of oxygen. Arsenic-based blood agents do so by causing red blood cells to burst, and cyanide-based blood agents do so by disrupting cellular processing of oxygen. Arsine, cyanogen chloride (CK), and hydrogen cyanide (AC) are colorless gasses, while sodium cyanide (NaCN) and potassium cyanide (KCN) are crystalline. Hydrogen cyanide (CK) was used as a genocidal agent by Nazi Germany, and may have also been used by Iraq during the Iran-Iraq War and against the Kurdish city of Halabja. At high doses, death from cyanide poisoning occurs within minutes.

- Mustard (HD)

- Mustard is a blister agent, or vesicant. The term mustard gas typically refers to sulfur mustard (HD), despite HD being neither a mustard nor a gas. Sulfur mustard gained notoriety during World War I for causing more casualties than all of the other chemical agents combined. Victims develop painful blisters on their skin, as well as lung and eye irritation leading to potential pulmonary edema and blindness. However, mustard exposure is usually not fatal. A liquid at room temperature, sulfur mustard has been delivered using artillery shells and aerial bombs. HD is closely related to the nitrogen mustards (HN-1, HN-2, HN—3).

- Lewisite (L)

- Lewisite is a blister agent that like mustard causes eye, skin, and airway irritation, but unlike mustard, acts immediately rather than with a delay. With significant exposure, lewisite can cause blindness. A colorless liquid, lewisite can be dispersed as a gas or a liquid. Lewisite (L) has no known medical or other non-military uses. Several countries, including Japan, the United States, and the Soviet Union, have produced and stockpiled lewisite. Lewisite may have been used by Japan during World War II.

- Diphosgene

- Diphosgene: A choking agent, diphosgene causes lung irritation leading to the build-up of fluid in the lungs. A colorless liquid at room temperature, diphosgene, like phosgene, smells like hay or young corn, and was delivered using artillery shells during World War I.

- Adamsite

- Adamsite: A chemical agent that causes eye, nose, and respiratory tract irritation in addition to vomiting and diarrhea. Classified as a vomiting agent, adamsite is odorless and usually enters the body by inhalation. Upon entering the body, adamsite poisoning begins within minutes and lasts up to several hours. First synthesized in 1918, adamsite was used by the Japanese during World War II. While some have stockpiled adamsite as a riot-control agent, the OPCW Scientific Advisory Board recommends against such use.

- Diphenylchloroarsine (DA)

- A vomiting agent, DA can be used as a riot-control agent or to force enemies to remove their protective gear. A white odorless crystal, DA and other vomiting agents are typically delivered as aerosols. Currently, DA is less prominent than other more easily weaponized agents.

- Chloracetophenone (CN)

- Chloracetophenone (CN): Distributed under the trade name Mace, CN is a tear agent that, as a solid or powder, can be delivered as smoke, powder, or liquid. CN produces eye irritation and tearing, as well as respiratory irritation. CN is typically used as a riot control agent, and is rarely lethal.

- CS

- CS: A widely used riot-control agent (RCA) and the standard RCA of the U.S. Army. CS causes tearing and a burning sensation in the eyes, as well as respiratory irritation and tightness. Skin exposure results in tingling or burning. CS is a white solid and can be dispersed in powdered form, as a liquid solution, or as smoke. CS is rarely lethal, and is considered to be both a more effective and less toxic RCA than CN.

- Tabun (GA)

- Tabun (GA): A nerve agent, tabun was the first of the nerve agents discovered in Germany in the 1930s. One of the G-series nerve agents, Nazi Germany produced large quantities of tabun but never used it on the battlefield. Tabun causes uncontrollable nerve excitation and muscle contraction. Ultimately, tabun victims suffer death by suffocation. As with other nerve agents, tabun can cause death within minutes. Tabun is much less volatile than sarin (GB) and soman (GD), but also less toxic.

- Sarin (GB)

- Sarin (GB): A nerve agent, sarin causes uncontrollable nerve cell excitation and muscle contraction. Ultimately, sarin victims suffer death by suffocation. As with other nerve agents, sarin can cause death within minutes. Sarin vapor is about ten times less toxic than VX vapor, but 25 times more toxic than hydrogen cyanide. Discovered while attempting to produce more potent pesticides, sarin is the most toxic of the four G-series nerve agents developed by Germany during World War II. Germany never used sarin during the war. However, Iraq may have used sarin during the Iran-Iraq War, and Aum Shinrikyo is known to have used low-quality sarin during its attack on the Tokyo subway system that killed 12 people and injured hundreds.

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

- The North Atlantic Treaty Organization is a military alliance that was formed in 1949 to help deter the Soviet Union from attacking Europe. The Alliance is based on the North Atlantic Treaty, which was signed in Washington on 4 April 1949. The treaty originally created an alliance of 10 European and two North American independent states, but today NATO has 28 members who have committed to maintaining and developing their defense capabilities, to consulting on issues of mutual security concern, and to the principle of collective self-defense. NATO is also engaged in out-of-area security operations, most notably in Afghanistan, where Alliance forces operate alongside other non-NATO countries as part of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). For additional information, see NATO.

- Warsaw Pact

- Warsaw Pact: Created in 1955 by the Soviet Union and its six Central European satellites, this military and political security alliance was the counterpart of NATO. It was formally dissolved on 1 April 1991.

- Binary chemical weapon

- A munition in which two or more relatively harmless chemical substances, held in separate containers, react when mixed or combined to produce a more toxic chemical agent. The mixing occurs either in-flight, for instance in a chemical warhead attached to a ballistic missile or gravity bomb, or on the battlefield immediately prior to use. The mechanism has significant benefits for the production, transportation and handling of chemical weapons, since the precursor chemicals are usually less toxic than the compound created by combining them. Binary weapons for sarin and VX are known to have been developed; or

A munition containing two toxic chemical agents. The United Kingdom combined chlorine and sulfur chloride during World War I and the United States combined sulfur mustard and lewisite. This definition is less commonly used. - Nerve agent

- A nerve agent is a chemical weapon that attacks the human nervous system, leading to uncontrolled nerve cell excitation and muscle contraction. Specifically, nerve agents block the enzyme cholinesterease, so acetylcholine builds up in the nerve junction and the neuron cannot return to the rest state. Nerve agents include the G-series nerve agents (soman, sarin, tabun, and GF) synthesized by Germany during and after World War II; the more toxic V-series nerve agents (VX, VE, VM, VG, VR) discovered by the United Kingdom during the 1950s; and the reportedly even more toxic Novichok agents, developed by the Soviet Union between 1960 and 1990. The development of both the G-series and V-series nerve agents occurred alongside pesticide development.

- VX

- VX: The most toxic of the V-series nerve agents, VX was developed after the discovery of VE in the United Kingdom. Like other nerve agents, VX causes uncontrollable nerve excitation and muscle excitation. Ultimately, VX victims suffer death by suffocation. VX is an oily, amber-colored, odorless liquid.

- Tactical nuclear weapons

- Short-range nuclear weapons, such as artillery shells, bombs, and short-range missiles, deployed for use in battlefield operations.

- Scud

- Scud is the designation for a series of short-range ballistic missiles developed by the Soviet Union in the 1950s and transferred to many other countries. Most theater ballistic missiles developed and deployed in countries of proliferation concern, for example Iran and North Korea, are based on the Scud design.

- Bilateral

- Bilateral: Negotiations, arrangements, agreements, or treaties that affect or are between two parties—and generally two countries.

- Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC)

- The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) requires each state party to declare and destroy all the chemical weapons (CW) and CW production facilities it possesses, or that are located in any place under its jurisdiction or control, as well as any CW it abandoned on the territory of another state. The CWC was opened for signature on 13 January 1993, and entered into force on 29 April 1997. For additional information, see the CWC.

- Blister agent

- Blister agents (or vesicants) are chemical agents that cause victims to develop burns or blisters (“vesicles”) on their skin, as well as eyes, lungs, and airway irritation. Blister agents include mustard, lewisite, and phosgene, and are usually dispersed as a liquid or vapor. Although not usually fatal, exposure can result in severe blistering and blindness. Death, if it occurs, results from neurological factors or massive airway debilitation.

- Nonproliferation

- Nonproliferation: Measures to prevent the spread of biological, chemical, and/or nuclear weapons and their delivery systems. See entry for Proliferation.

- Safeguards

- Safeguards: A system of accounting, containment, surveillance, and inspections aimed at verifying that states are in compliance with their treaty obligations concerning the supply, manufacture, and use of civil nuclear materials. The term frequently refers to the safeguards systems maintained by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in all nuclear facilities in non-nuclear weapon state parties to the NPT. IAEA safeguards aim to detect the diversion of a significant quantity of nuclear material in a timely manner. However, the term can also refer to, for example, a bilateral agreement between a supplier state and an importer state on the use of a certain nuclear technology.

See entries for Full-scope safeguards, information-driven safeguards, Information Circular 66, and Information Circular 153. - Disarmament

- Though there is no agreed-upon legal definition of what disarmament entails within the context of international agreements, a general definition is the process of reducing the quantity and/or capabilities of military weapons and/or military forces.

- G-8 Global Partnership Against the Spread of Weapons of Mass Destruction

- Launched in 2002 at the G-8 Summit in Kananaskis, the G-8 Global Partnership is a multilateral initiative for financial commitments to implement and coordinate chemical, biological, and nuclear threat reduction activities on a global scale. Originally granted a ten-year lifespan and focused primarily on activities in the former Soviet Union, the Partnership has since been extended beyond 2012; it has also expanded its membership and scope of activities globally. For additional information, see the G-8 entry in the NTI Inventory.

- Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW)

- The OPCW: Based in The Hague, the Netherlands, the OPCW is responsible for implementing the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC). All countries ratifying the CWC become state parties to the CWC, and make up the membership of the OPCW. The OPCW meets annually, and in special sessions when necessary. For additional information, see the OPCW.

- Dismantlement

- Dismantlement: Taking apart a weapon, facility, or other item so that it is no longer functional.

- Ballistic missile

- A delivery vehicle powered by a liquid or solid fueled rocket that primarily travels in a ballistic (free-fall) trajectory. The flight of a ballistic missile includes three phases: 1) boost phase, where the rocket generates thrust to launch the missile into flight; 2) midcourse phase, where the missile coasts in an arc under the influence of gravity; and 3) terminal phase, in which the missile descends towards its target. Ballistic missiles can be characterized by three key parameters - range, payload, and Circular Error Probable (CEP), or targeting precision. Ballistic missiles are primarily intended for use against ground targets.

Sources

- "A New Legal Framework for U.S.-Russian Cooperation in Nuclear Nonproliferation and Security," U.S. Department of State, 19 June 2013, www.state.gov.

- Lev Fedorov, "Контрольная для взрослых. "Химическое разоружение за счет людей" [Khimicheskoe razoruzhenie za schet lyudei - Chemical weapon disarmament on account of the people], Неприкосновенный запас [Neprikosnovennyi zapas - Iron rations] 2006, №2 (46), www.magazines.russ.ru/nz.

- "Советский химический арсенал" [Sovetskii khimicheskii arsenal - Soviet chemical arsenal], Международный социально экологический союз [Mezhdunarodnyi sotsial'no-ekologicheskii soyuz - International social-ecological union], Accessed 3 March 2014, www.seu.ru.

- "Военная академия радиационной, химической и биологической защиты им. Маршала Советского Союза С.К. Тимошенко" [Voennaia akademiia radiatsionnoi, khmicheskoi I biologicheskoi zashchity im. Marshala Sovetskogo Soyuza S.K. Timoshenko - Military academy of radiological, chemical and biological defense, named after Marshall of the Soviet Union S.K. Timoshenko], Министерство обороны Российской Федерации [Ministerstvo oborony Rossiiskoi Federatsii - Ministry of defense of the Russian Federation] Accessed 3 March 2014, www.mil.ru.

- Sergei Linnik, "Химическое оружие. Ликвидация или совершенствование?" [Khemicheskoe oruzhie. Likvidatsiia ili soverwhenstvovanie? - Chemical weapons, Liquidation or improvement?] Военное обозрение [Voennoe obozrenie - Military review], 1 November 2013, www.topwar.ru.

- Lev Fedorov, "Chemical Weapons in Russia: History, Ecology, Politics," Federation of American Scientists, Accessed 3 March 2014, www.fas.org.

- Thomas S. Bundt, "Gas, Mud, and Blood at Ypres: The Painful Lessons of Chemical Warfare," Military Review, July-August 2004, p. 81.

- Gerald J. Fitzgerald, "Chemical Warfare and Medical Response During World War I," American Journal of Public Health, April 2008, Vol 98, No. 4, p. 615.

- Joachim Krause and Charles K. Mallory, Chemical weapons in Soviet military doctrine: military and historical experience, 1915-1991, (Boulder: Westview Press, 1992) pp. 18-19.

- Robert J. T. Joy, "Chapter 3: Historical Aspects of Medical Defense Against Chemical Warfare" from Medical Aspects of Chemical and Biological Warfare, (Office of the Surgeon General, Borden Institute), 1997, p. 101.

- Victoria Utgoff, The Challenge of Chemical Weapons: An American Perspective, (New York: St. Martins Press, 1990) p. 42.

- Augustin Mitchell Prentiss, Chemicals in War: a Treatise on Chemical Warfare (New York: McGraw-Hill Books, 1937).

- Augustin Mitchell Prentiss, Chemicals in War: a Treatise on Chemical Warfare (New York: McGraw-Hill Books, 1937).

- Joachim Krause and Charles K. Mallory, Chemical Weapons in Soviet Military Doctrine: Military and Historical Experience, 1915-1991, (Boulder: Westview Press, 1992) p. 20.

- Joachim Krause and Charles K. Mallory, Chemical Weapons in Soviet Military Doctrine: Military and Historical Experience, 1915-1991, (Boulder: Westview Press, 1992) p. 4.

- Victoria Utgoff, The Challenge of Chemical Weapons: An American Perspective, (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1990) p. 42.

- Joachim Krause and Charles K. Mallory, Chemical Weapons in Soviet Military Doctrine: Military and Historical Experience, 1915-1991, (Boulder: Westview Press, 1992) pp. 36.

- The Versailles Treaty, Part V, Article 171, June 28, 1919, (The Avalon Project, Yale Law School), Accessed 3 March 2014, http://avalon.law.yale.edu.

- Joachim Krause and Charles K. Mallory, Chemical Weapons in Soviet Military Doctrine: Military and Historical Experience, 1915-1991, (Boulder: Westview Press, 1992) pp. 36-37.

- The Problem of Chemical and Biological Warfare: The Rise of CB Weapons, Volume 1, (New York: Humanities Press, 1971) pp. 246.

- Victoria Utgoff, The Challenge of Chemical Weapons: An American Perspective, (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1990) pp. 42-45.

- Victoria Utgoff, The Challenge of Chemical Weapons: An American Perspective, (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1990) pp. 42-45.

- The Problem of Chemical and Biological Warfare: The Rise of CB Weapons, Volume 1, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, (New York: Humanities Press, 1971) pp. 323-324.

- Victoria Utgoff, "The Challenge of Chemical Weapons: An American Perspective," (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1990).

- Jonathon Tucker, War of Nerves, (Anchor Books; New York; 2006) pp. 232-233; D. Hank Ellison, Handbook of Chemical and Biological Warfare Agents, Second Edition, (Boca Raton: Taylor and Francis Group, 2008) p. 70.

- Joachim Krause and Charles K. Mallory, Chemical Weapons in Soviet Military Doctrine: Military and Historical Experience, 1915-1991, (Boulder: Westview Press, 1992) p. 116.

- Jonathon Tucker, War of Nerves, (Anchor Books; New York; 2006) pp. 232-233; D. Hank Ellison, Handbook of Chemical and Biological Warfare Agents, Second Edition, (Boca Raton: Taylor and Francis Group, 2008) pp. 106-107.

- Shirley D. Tuorinsky, Ed., Medical Aspects of Chemical Warfare (Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General, 2008).

- Joachim Krause and Charles K. Mallory, Chemical Weapons in Soviet Military Doctrine: Military and Historical Experience, 1915-1991, (Boulder: Westview Press, 1992) p. 144.

- Joachim Krause and Charles K. Mallory, Chemical Weapons in Soviet Military Doctrine: Military and Historical Experience, 1915-1991, (Boulder: Westview Press, 1992) p. 128.

- Corey J. Hilmas, Jeffrey K. Smart, and Benjamin A. Hill, JR, "History of Chemical Warfare," in Shirley D. Tuorinsky, Ed., Medical Aspects of Chemical Warfare, (Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General, 2008).

- Corey J. Hilmas, Jeffrey K. Smart, and Benjamin A. Hill, JR, "History of Chemical Warfare," in Shirley D. Tuorinsky, Ed., Medical Aspects of Chemical Warfare, (Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General, 2008).

- V.D. Sokolovskiy, Military Strategy, (1st edition, Voyenizdat, Moscow, 1962).

- Chemical Weapons, Federation of American Scientists, Accessed 9 February 2013, www.fas.org.

- Joachim Krause and Charles K. Mallory, Chemical Weapons in Soviet Military Doctrine: Military and Historical Experience, 1915-1991, (Boulder: Westview Press, 1992) p. 156; David Hoffman, The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and its Dangerous Legacy, (New York: Doubleday, 2009) p. 310.

- Federation of American Scientists, Chemical Weapons, Accessed 9 February 2013; Lev Aleksandrovich Fedorov, Chemical Weapons in Russia: History, Ecology, Politics, Federation of American Scientists, Accessed 27 July 1994, www.fas.org.

- David Hoffman, The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and its Dangerous Legacy, (New York: Doubleday, 2009) p. 310.

- Jonathon Tucker, War of Nerves, (Anchor Books; New York; 2006) p.232-233; D. Hank Ellison, Handbook of Chemical and Biological Warfare Agents, Second Edition, (Boca Raton: Taylor and Francis Group, 2008) p. 6.

- United States Department of the Army, The Soviet Army: Operations and Tactics, (Washington, DC, 1984), pp. 2-10.

- Director of Central Intelligence, Implications of Soviet Use of Chemical and Toxin Weapons for US Security Interests (Special National Intelligence Estimate, SNIE 11-17-83), 15 September 1983, Declassified 28 February 1994.

- United States Department of the Army, The Soviet Army: Operations and Tactics, (Washington, DC, 1984), pp. 2-10.

- United States Department of the Army, The Soviet Army: Operations and Tactics, (Washington, DC, 1984), pp. 2-10.

- United States Department of the Army, The Soviet Army: Operations and Tactics, (Washington, DC, 1984), pp. 2-10.

- United States Department of the Army, The Soviet Army: Operations and Tactics, (Washington, DC, 1984), pp. 2-10.

- Director of Central Intelligence, Implications of Soviet Use of Chemical and Toxin Weapons for US Security Interests (Special National Intelligence Estimate), SNIE 11-17-83, September 15, 1983, Declassified 28 February 1994.

- Brad Knickerbocker, "Does the USSR Use Chemical Warfare? Christian Science Monitor, 1 December 1982, www.csmonitor.com.

- Corey J. Hilmas, Jeffrey K. Smart, and Benjamin A. Hill, JR, "History of Chemical Warfare," in Shirley D. Tuorinsky, Ed., Medical Aspects of Chemical Warfare (Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General, 2008) p. 62.

- Joseph J. Collins, "The Soviet Military Experience in Afghanistan," Military Review, 1985, p. 65.

- Director of Central Intelligence, Implications of Soviet Use of Chemical and Toxin Weapons for US Security Interests (Special National Intelligence Estimate), SNIE 11-17-83, September 15, 1983, Declassified 28 February 1994.

- David Hoffman, The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and its Dangerous Legacy, (New York: Doubleday, 2009) pp. 309-310.

- Federation of American Scientists, Chemical Weapons, Accessed 9 February 2013, www.fas.org.

- Federation of American Scientists, Chemical Weapons, Accessed 9 February 2013, www.fas.org.

- Federation of American Scientists, Chemical Weapons, Accessed 9 February 2013, www.fas.org.

- Federation of American Scientists, Chemical Weapons, Accessed 9 February 2013, www.fas.org.

- Amy E. Smithson, Toxic Archipelago: Preventing Proliferation from the Former Soviet Chemical and Biological Weapons Complexes, (Washington, D.C.: Stimson Center, 1999) p. 11.

- Amy E. Smithson, Toxic Archipelago: Preventing Proliferation from the Former Soviet Chemical and Biological Weapons Complexes, (Washington, D.C.: Stimson Center, 1999) p. 9.

- "Fact Sheet: The Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Program," (American Security Project: 2012), Accessed 28 February 2014, www.americansecurityproject.org.

- Michael Jasinski, Nonproliferation Assistance to Russia and the New Independent States, (Nuclear Threat Initiative: 1 August 2001), www.nti.org.

- Ashton B. Carter and William J. Perry, Preventive Defense: A New Security Strategy for America, (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 1999) pp. 74-75.

- The United States Department of State, Office of Cooperative Threat Reduction (ISN/CTR) Mission Statement, Accessed 28 February 2014, www.state.gov.

- International Science and Technology Center in Moscow, "Who We Are and What We Do," www.istc.ru.

- Amy E. Smithson, Toxic Archipelago: Preventing Proliferation from the Former Soviet Chemical and Biological Weapons Complexes, Report No. 32, (Washington, DC: Stimson Center, 1999) p. 9.

- Will Englund, "Ex-Soviet Scientist Says Gorbachev's Regime Created New Nerve Gas in '91," Baltimore Sun, 16 September 1992.

- Accuracy of Russia's Report on Chemical Weapons, ESDN: 0001239709, (Central Intelligence Agency Freedom of Information Act) pp. 6-7.

- Richard Boudreax, "Yeltsin Fires Chemical Warfare Chief," LA Times, 8 April 1994, www.latimes.com.

- Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, "Overview of the Chemical Weapons Convention," Accessed 11 February 2013, www.opcw.org.

- National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1997, Public Law 104-201, 23 September 1996, p. 110 STAT. 2730 and 2732; Amy E. Smithson, Toxic Archipelago: Preventing Proliferation from the Former Soviet Chemical and Biological Weapons Complexes, (Washington, D.C.: Stimson Center, 1999) pp. 78-79.

- National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1997, Public Law 104-201, 23 September 1996, p. 110 STAT. 2732.

- Kenneth N. Luongo and William E. Hoehn III, Reform and Expansion of Cooperative Threat Reduction, (Washington, DC: Arms Control Association, 2003), Accessed 28 February 2014, www.armscontrol.org.

- "Decision: Request from the Russian Federation for Conversion of a Chemical Weapons Production Facility for Purposes not Prohibited under the Convention," Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, 29 June 1999; "Decision: Request from the Russian Federation for Conversion of a Chemical Weapons Production Facility (Mustard Gas Production Facility) for Purposes not Prohibited under the Convention," Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, 17 May 2000; "Decision: Request from the Russian Federation for Approval to use a Chemical Weapons Production Facility for Purposes not Prohibited under the Convention," Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, 10 October 2002.

- "Russian Federation Unveils the Gorny Chemical Weapons Destruction Plant," Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, 28 August 2002; "Russian Federation Officially Begins Chemical Weapons Destruction at New Site in Maradykovsky," Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons: 8 September 2006; "OPCW Director-General Attends Opening Ceremony of the Shchuchye Chemical Weapons Destruction Facility in the Russian Federation," Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, May 29, 2009; "Update on Chemical Demilitarization," Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, 21 April 2009, www.opcw.org.

- "OPCW Director-General Attends Opening Ceremony of the Shchuchye Chemical Weapons Destruction Facility in the Russian Federation," Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, 29 May 2009, www.opcw.org.

- Министерство инностранных дел Российской Федерации [Ministerstvo innostrannykh del Rossiiskoi Federatsii - The Russian Federations' Ministry of Foreign Affairs], "Комментарий Департамента информации и печати МИД России по вопросу о сроке действия «Программы Нанна-Лугара»" [Kommentarii Departmenta informatsii i pechati MID Rossii po voprosu o sroke deistviia "Programmy Nanna-Lugara" - The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs' Department of information and press' commentary about the Nunn-Lugar Program's term of action], 10 October 2012, www.mid.ru.

- David M. Herszenhorn, "Russia Won't Renew Pact on Weapons with U.S," New York Times, 10 October 2012, www.nytimes.com.

- The United States Department of State, "A New Legal Framework for U.S.-Russian Cooperation in Nuclear Nonproliferation and Security," Washington D.C., 19 June 2013, www.state.gov.

- Sam Kane, "The Sun Sets on Nunn-Lugar in Russia," Nukes of Hazard, 21 June 2013, www.nukesofhazardblog.com.

- Justin Bresolin, "Fact Sheet: The Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Program," The Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation, July 2013, www.armscontrolcenter.org.

- "New Chemical Weapons Destruction Facility Opens at Kizner in the Russian Federation," Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, 20 December 2013, www.opcw.org.

- "Russia Eliminates 86% of Chemical Weapons Stockpile — OPCW Chief," TASS Russian News Agency, 18 March 2015, tass.ru/en.

- "Russia to Complete Chemical Weapons Destruction at 4 of 5 Facilities by End of 2015," TASS Russian News Agency, 30 January 2015, tass.ru/en.

- "Statement by the delegation of the Russian Federation at the Nineteenth Session of the Conference of the States Parties," Statement by the Russian Delegation, Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, 1 December 2014, www.opcw.org.